Every year on Nov. 11, people across Canada gather in front of their community’s cenotaph to pay their respects to the memory of their war dead. The word 'cenotaph' has its origin in Greek, and means 'empty tomb.'

In the aftermath of the First World War, a decision was made that it was not possible to repatriate the remains of the thousands of Canadians who had died overseas. Instead, cities and towns would erect cenotaphs to honour those who lay in foreign graves – or no graves at all – as well as the many who returned home from the war but who died because of war-related injuries or illness.

There was hardly a place in the country that had not been touched by wartime loss, and so in almost every community in every county, the cenotaphs went up. For various reasons, usually to do with local funding, some communities took longer than others.

In Wellington County, Belwood, Palmerston and Rockwood erected cenotaphs in 1919. Puslinch Township followed in 1920. Monuments were unveiled in Clifford, Harriston and Nichol Township in 1921. Arthur got one in 1923; Drayton and Guelph in 1927, Mount Forest in 1928, and Elora in 1929. Meanwhile, there was no cenotaph in Fergus. (Erin wouldn’t get one until 1956.) It is true that there is a story behind every name on a cenotaph, but the story of how Fergus got its cenotaph is unique in itself.

Perhaps no one in Fergus was more unhappy about the town’s lack of a cenotaph than Dr. Norman M. Craig, who was himself a veteran of the Great War.

Born in Fergus in 1895, Craig had been in the militia as a youth and was in medical school when the war broke out in 1914. He enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in March of 1915 and served in the eastern theatre of the war as a medic. Then he transferred to the Royal Naval Air Service and became a flying officer, leading a squadron of Sopwith Camel fighter planes out of a base on a strategically located Greek island.

After the war, Craig continued with his medical studies and graduated. By the early 1930s he was a prominent physician and leading citizen in Fergus. He deplored the fact that men from Fergus – some of them his own childhood friends – who had given their lives in places like Ypres, the Somme and Vimy Ridge, were not remembered the way other fallen Canadians were. He was determined that they should have a monument to their memory.

The question of a cenotaph for Fergus had been raised on more than one occasion, but had always been voted down. Apparently, some people objected to the idea of something they believed would be a monument to war. To Craig, a cenotaph did not celebrate war; it honoured victims of war. Then, in 1932, there was a new obstruction; economics.

The whole country was suffering under the crush of the Great Depression. With widespread unemployment, and money in short supply at every social level, there were no funds for projects like a cenotaph. Craig came up with a solution to the problem. He would write a play, and the proceeds would go toward a cenotaph.

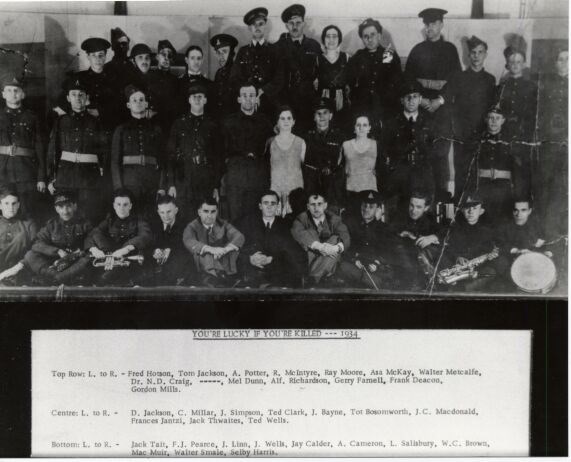

Craig wrote a play set in the Great War titled, You’re Lucky if You’re Killed. It has been called “the first Canadian war play.” Craig wrote the lyrics for original songs which he hoped would inspire audiences with “the nobleness, the grandeur and the sacrifice of our pals.” The doctor was not a composer of music, but he had some tunes in his head. He hummed them for his mother, who was a pianist. She then played the songs for a musician who knew notation.

Craig undertook the big job of producing the play himself. Actors and stage crew were all local amateur talent. Craig played the part of a pilot.

The play was performed in Fergus in June of 1933 and had an overwhelmingly positive reception from the audience. The response was so enthusiastic, that Craig wrote a letter to Universal Films, hoping some Hollywood mogul might want to make his play into a movie. His letter said, “It made them laugh, it made them cry … it scared them to death.”

You’re Lucky if You’re Killed didn’t make it to the silver screen, but it did serve the purpose for which it was written – raising money for the Fergus cenotaph. Following a dawn parade on Aug. 5, 1935, the memorial was unveiled in what was then called Union Square. The park is now named after Dr. Norman Craig, and an inscribed stone tells of his efforts to have a cenotaph erected in Fergus.