In November of 1950, Charles Meakins posed in his Elora home for a Guelph Mercury photographer. He stood in front of a framed poster from London, England’s famed Drury Lane Theatre Royal that featured his name in bold letters. In his hands he held a book containing dozens of press clippings about his performances.

It was one of several such books that today make up a summary of Meakins’ career as one of the best-known Canadian stage performers of his time. Those books are now owned by Eric Huber, who lives part-way between Elora and Guelph.

Charlesworth James Meakins was born in Hamilton on March 15, 1877. As a boy, he sang in the choir of Christ’s Church Cathedral and in local concerts. While in his early 20s, Meakins went to New York City on business entirely unrelated to singing and the theatre. There he met Broadway actress Edith Bradford, an accomplished singer and dancer whom he eventually married.

Edith saw talent in the young Canadian and introduced him to Augustin Daly, one of the most influential theatrical producers of the time. Daly gave Meakins an audition and then cast him in the plum role of Prince Danillo in The Merry Widow, an operetta by Franz Lehar.

The Merry Widow was a smash hit. Beginning in 1905, it played for seven years in North America, the United Kingdom and Continental Europe. In the Edwardian era, long before there were movie idols like Clark Gable or pop sensations like Elvis, Charles Meakins was a star. He was handsome, a gifted actor and singer, and according to the critics of the day, “the most graceful and active dancer on the operatic stage in America.”

Meakins was one of the reasons that The Merry Widow Waltz became a dance rage that swept society. Not only was he good looking, but the role of Prince Danillo was a physically demanding one that also kept him athletically fit.

“I maintain that in three hours I do as much work as the average laborer in ten hours,” Meakins told a Toronto Star reporter.

Meakins had an army of fans that included men and women of all ages, but a large percentage of his admirers were the young women who were known as “matinee girls.” Everyday he received letters from them requesting autographs, photographs, and the opportunity to meet him personally. The letters were usually almost painfully polite, begging him to excuse the intrusion on his time before asking him to favour the writer with a signed photo. Sometimes they began with “Dear Prince” or even “Dear Prince Charming.” Occasionally, the writer would be anonymous.

“The lady who sent you the gardenias in Richmond Virginia last winter sends you this today & wishes you ‘good luck.’”

Between engagements in large centres, the show played one-night stands in smaller communities – including one stop in Guelph. The matinee girls would address their letters to Meakins care of the theatre in which they’d seen him perform. The forwarding addresses on the envelopes show that sometimes a letter would follow Meakins from one theatre to another before finally catching up with him. According to a few of the letters, some of the matinee girls would go to see Meakins perform over and over.

Meakins once told a reporter he couldn’t possibly answer all the requests for photos. As a result, he occasionally received a follow-up letter from a disgruntled fan, curtly asking him if he couldn’t send a photo, could he at least tell the writer where to buy one.

Meakins’ books of memorabilia are also full of calling cards from the leading citizens of the cities in which he performed. Businessmen, socialites and presidents of prestigious community groups all left the actor invitations to dinner, requests to speak at special events and free passes to the facilities of private clubs. There are a few letters and cards from Meakins’ show business colleagues.

One letter was written by Wilfred Lucas, a stage actor and fellow Canadian who went on to be a screenwriter, actor and director in silent movies and then the “talkies.” When French movie star Maurice Chevalier was chosen to play Prince Danillo in a 1934 film production of The Merry Widow, one of Meakins’ friends wrote to tell him that he would have been better in the role.

For a while, Meakins even shared a residence with John Barrymore.

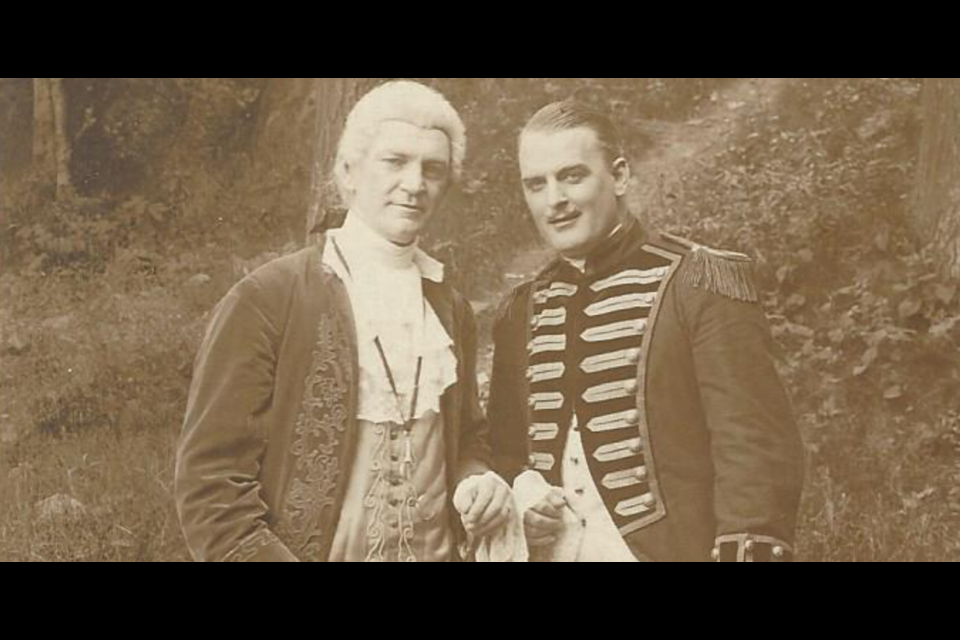

Meakins performed in dozens of other stage productions over his long career. Among them were Country Girl, Gay Hussars, Excuse Me, Little Boy Blue, Miss Springtime and The Million. Perhaps his most successful role, after The Merry Widow, was that of Sergeant Malone in Rose Marie. That show had a three-year run on Drury Lane that included a Royal Command performance.

Meakins credited Edith Bradford for getting him started in the theatre. “She taught me a great deal, gave me the groundwork, the basic principals of the stage business,” he said.

But his marriage to Edith didn’t last. In fact, Meakins was married three times.

His third wife was Gene Connon, whom he married in 1937 after retiring from the stage. She was born into a prominent Elora family. Her uncle, John Connon, was a well-known photographer and the author of a book on Elora history. When he died in 1931, Gene inherited his house on Geddes Street.

Charles and Gene lived for a while in Goderich, and then moved to Elora where the former stage star spent his last years. He made his final exit on May 4, 1951. According to newspaper accounts of the time, Meakins was interred in an Elora cemetery. But his name is also on a gravestone in a Hamilton cemetery, so his actual burial place is uncertain.

His legacy now lies between the covers of a few old volumes of letters and clippings.