In Belsyde Cemetery in Fergus there is a gravestone with the inscription “Thomson Beattie 1875-1912.” But Beattie is not buried there. By an ironic twist of fate, he went to his final rest in the place where his mother, Janet, had been born 82 years earlier, the open sea of the North Atlantic.

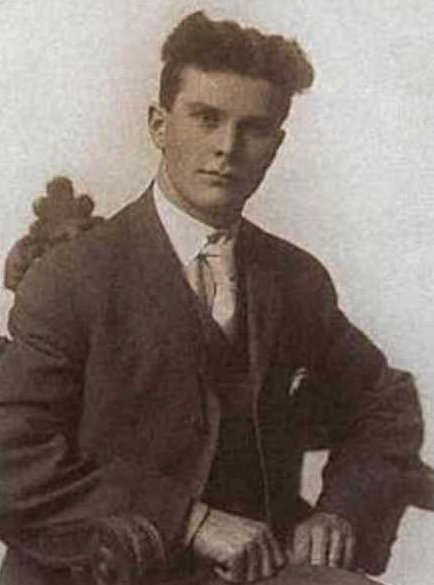

Fergus-born Thomson Beattie was a passenger aboard RMS Titanic. How did a man from Fergus wind up on the doomed ocean liner?

In the spring of 1830, Janet Boyd Wilson’s family joined the wave of Scottish immigration to Canada. She was born on the ship Justinian somewhere on the mid-Atlantic on May 15. With a new baby in the family, the Wilsons settled in Fergus in what was then called Upper Canada. In 1850, Janet married John T. Beattie, a young man who had been an agent for the Royal Canadian Bank. Now he opened his own private financial enterprise, Beattie’s Banking House. In 1871, he became the Clerk for Wellington County, a position he held until his death in 1897.

Thomson Beattie was born on November 25, 1875, the youngest of John and Janet’s eleven children. There were 24 years between him and his oldest brother, William. Thomson had a Presbyterian upbringing. In addition to his regular schooling, he was an apprentice in his father’s bank and trained to be an accountant.

A year after John’s death, Thomson and his brother Charles moved to Winnipeg and went into business for themselves. Winnipeg at that time was the transportation, commercial and financial centre for Western Canada, and was a boomtown. Beattie formed a partnership in the real estate business with a young entrepreneur named Richard Waugh. Their Haslam Land Company was a great success. Within a few years, Beattie could afford to live in a house in one of Winnipeg’s most affluent residential districts.

In 1911, Waugh was elected mayor of Winnipeg, leaving Beattie to manage their business affairs. Beattie preferred to keep a low profile socially, and was something of an enigma to all but a few close friends. He was not married, and was considered one of Winnipeg’s most eligible bachelors. His two best friends were Thomas McCaffry, a banker; and John Hugo Ross, a real estate colleague who was former secretary to Manitoba’s lieutenant-governor.

Beattie, McCaffry and Ross decided to go on a long holiday that would take them to Italy, Egypt, the Middle East, France and England. On January 20 they sailed from New York on the Cunard ocean liner Franconia, bound for Trieste. Also aboard the ship was another Winnipeg real estate businessman, Mark Fortune, who was vacationing with his wife and four of their six children.

Beattie mailed home photographs from places like Luxor and Vienna that showed him and his companions enjoying their tour. But by the time they arrived in Paris in March, Ross had fallen ill. McCaffry and Beattie were weary of travelling and wanted to go home. They wrote on a postcard to a friend that they were “ready for Winnipeg and business.”

The three men continued on to London and were booked aboard a ship for their trip home when they had a sudden change of plans. Beattie wrote to his mother in Fergus, “We are changing ships and coming home in a new, unsinkable boat.”

Fate had put Beattie and his companions aboard the Titanic. He and McCaffry shared cabin C-6 in the first-class section, for which they paid 75 pounds, four shillings and ten pence – a lot of money at that time. Ross was so ill, he had to be carried onto the ship on a stretcher. He had a cabin to himself. The Fortune family was also aboard. Beattie almost certainly would have run into fellow first-class passengers Lady Duff Gordon – formerly Lucy Sutherland of Guelph – the famous socialite and fashion designer, and her husband Cosmo.

It is known from reports given later that Ross, who was bed-ridden, never left his cabin during the voyage. Beattie was somewhat indisposed by seasickness, but on the fateful night of April 15 he and McCaffry were in formal attire in the Georgian Smoking Room when the Titanic struck an iceberg and began to sink. When Ross was first told of the collision, he didn’t understand the seriousness of the situation. “It will take more than an iceberg to get me out of my bed,” he said, and went back to sleep.

The story of what happened that night has been told and retold in books and on film. There were not enough lifeboats on the “unsinkable” ship for all of the people on board. Some of the lifeboats that were successfully launched did not carry as many people as they could have.

Beattie was among about twenty people who managed to get into one of the last lifeboats to leave the sinking Titanic, but that boat was swamped. The people in it were sitting in two feet of freezing cold water. Their lower bodies grew numb, and some of them succumbed to hypothermia. One by one, the bodies of the dead were thrown overboard to lighten the boat.

Beattie seemed to be unconscious. A passenger named Ole Abelseth tried to keep him alive by holding and shaking him, but Beattie muttered, “Let me be. Who are you?”

The lifeboat drifted until dawn, when it was spotted by a ship’s officer in another boat that still had room in it. The survivors were picked up, but Beattie and two other people were dead. The bodies were left in the boat. Ross and McCaffry were also lost, as were Mark Fortune and one of his sons.

In the hours after the disaster, ships picked up many of the Titanic’s dead, but the lifeboat containing the bodies of Beattie and two other victims drifted on the sea for a month. On May 15, it was found by the liner Oceanic. The crew gave the three dead men a formal burial at sea. To add to the irony of the occasion, it was Beattie’s mother’s birthday.