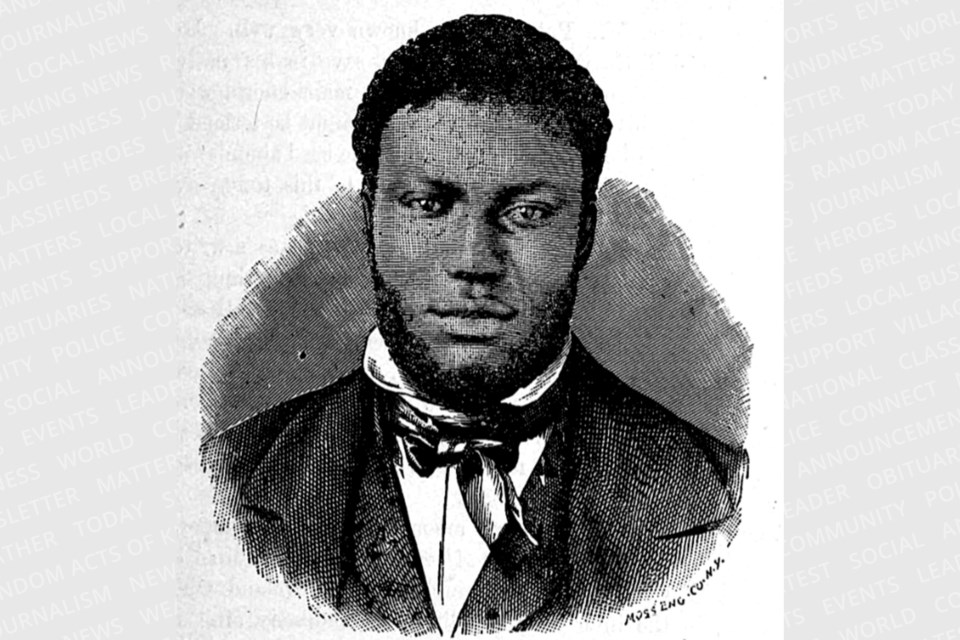

In June of 1852, a man committed to the cause of ending slavery in the United States made a speech in Elora. His name was Samuel Ringgold Ward. By his presence in Elora, he connected the little community to one of the greatest social issues of the day.

Ward was born to enslaved parents in Maryland in 1817. When he was three years old his mother and father fled from bondage, heading first for New Jersey but then settling in New York. Young Samuel was educated by Quakers, who were strong proponents of the abolition of slavery.

He became a clergyman and was pastor to both black and white congregations. Ward also studied medicine and law.

Initially, “Free states” like New Jersey and New York were legally safe territory for escaped slaves – as long as they could avoid being abducted by “slave catchers” and dragged back to the South.

Then in 1850, under pressure from Southern politicians, the American federal government passed the Fugitive Slave Act. That legislation meant that Southern slave catchers could legally apprehend former slaves in Free states and return them to the South. In fact, even African Americans who had been born free were in danger of being seized and carried off to slavery.

All it took was for one unscrupulous white person to swear before a judge that the unfortunate victim was a fugitive slave.

With the free states of the American North no longer safe ground, many people fleeing slavery now travelled the secret routes of the Underground Railroad to Canada, where slavery had long since been outlawed. Because angry Southern slave owners could not legally recover their “property” once

the escapees had crossed the international border, they called that northern sanctuary “the vile, sensuous, animal, infidel, superstitious Democracy of Canada.”

Samuel Ringgold Ward had for years been an outspoken abolitionist, as well as an advocate for temperance. His famous colleague, Frederick Douglass, considered him one of the great orators of the day. He was an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, a member of the Liberty Party and an editor

for two publications, the True American and Religious Examiner and the Impartial Citizen.

In 1851, Ward participated in helping a captured fugitive slave named William Henry escape from jail in Syracuse, New York, and cross the border into Canada. A warrant was issued for Ward’s arrest, so he fled to Toronto. He vowed he would never return to the United States, stating that the Americans had betrayed their vision of freedom and democracy.

He also said that the Southern slavocracy wielded too much political power in the U.S.

However, Ward discovered that even though Canada did not have the evil of slavery, it was not free from the curse of racism. Not everybody in Canada welcomed the fugitives from Southern bondage. Black people in Canada found themselves discriminated against in many situations including employment and housing.

Ward’s own family, when travelling by train from Montreal to Toronto and by ship on Lake Ontario, were obliged to accept segregated accommodations so as not to “offend” white passengers with their presence.

Dealing with bigotry in Canada would take many years of work and patience. Ward blamed much of the discrimination he encountered in Canada on American influence.

Ward quickly became involved with organizations in both the black and white communities that were trying to help formerly enslaved people establish themselves in their new home. He assisted Mary Ann Shadd, the black woman who was Canada’s first female publisher, by lending his name to her publication, The Provincial Freeman.

Ward visited St. Catharines, which was reputed to be a hotbed of anti-black bigotry, and reported the negative reputation was undeserved. Ward sometimes clashed with other high-profile black leaders due to conflicting views on how the new arrivals should adjust to Canadian society.

The Canadian Anti-Slavery Society invited Ward to work with them as an agent and lecturer. A speaking tour was arranged that would take him across much of what is now Southern Ontario. His stops included urban centres such as Kingston, Windsor, Hamilton and London where he’d be heard by more people and there would be greater opportunities to solicit donations for the cause.

However, he and the society were also aware of the importance of him appearing in smaller communities out in the countryside where many of the black immigrants had settled.

Rev. Solomon Waldron, a Methodist Episcopal minister assigned to Elora, arranged to have Ward come to town. As an agricultural supply centre and the location of a land office, Elora drew visitors from beyond the borders of Wellington County. It was therefore a logical place for Ward to deliver one of his eloquent speeches.

There does not appear to be any known record of exactly what Ward said in Elora, but going by what he said in other communities he visited on that tour, historians have a reasonably good idea of what he talked about.

Ward believed instead of segregating themselves from white Canadian communities and living in their own settlements, as some of the other black leaders advised, the newcomers should integrate into Canadian society. He believed they should, wherever possible, acquire land and establish farms, rather than just hire out as labourers.

Ward told his black listeners it was up to them to dispel the myth they were inferior to whites, and they could accomplish that through education, honesty, industriousness and temperance. He told his white listeners that black people, living as free citizens in a free society, had proven they were not a “dependent race.”

In 1853, the society sent Ward on a speaking and fundraising tour of England. According to an article published in the Toronto Globe under the heading “AID TO FUGITIVE SLAVES IN CANADA,” he “has made a most favourable impression, as to his talents and fitness for his mission.”

While in England, Ward published his life story, Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro.

Ward never returned to Canada. In 1855 he sailed to Jamaica where he served as a pastor at a church in Kingston and then settled on a farm. He had a controversial role in a rebellion that erupted there in 1865. Ward died in obscurity in 1866.

Ward’s visit to Elora was brief, but it nonetheless connected the little Canadian town to one of the most significant and dramatic stories in North American history, the fight against slavery.